Thus far, 2025 has been a year of unprecedented macroeconomic uncertainty, yet the American economy has shrugged off much of the anticipated consequences. The unemployment rate – though creeping up – remains well below historical averages at 4.3%. Inflation, a major post-pandemic headache for the Fed, has been largely tamed from its 2023 level. And in welcome news for retail and institutional investors alike, the S&P 500, NASDAQ Composite, and Dow Jones Industrial Average indices are all fresh off record highs.

Casting a shadow over this sustained resilience, however, are alarm bells ringing ever so louder, hinting at the looming prospect that hidden underlying economic weakness would ultimately catch up with American markets.

The Job Market

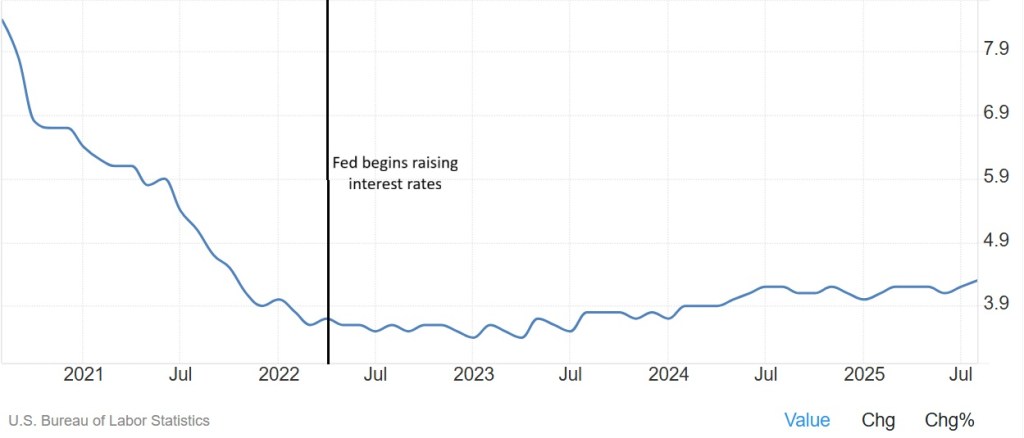

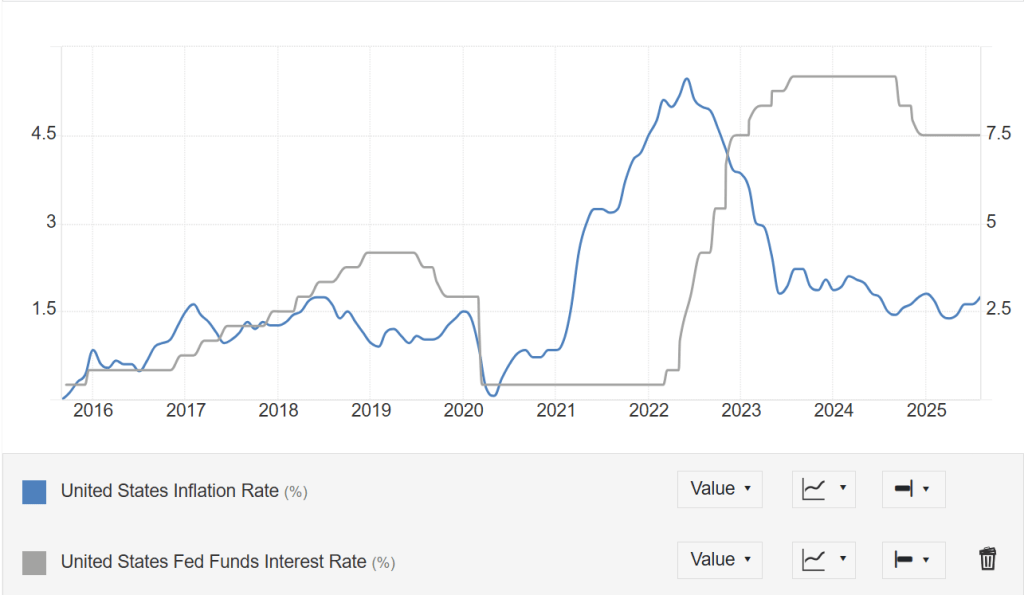

When US inflation skyrocketed in 2023, the Fed aggressively raised interest rates to a decade-high level of 5.25 – 5.50% in an effort to cool down the economy. In doing this, its governors braced for the possibility of deteriorating the labour market, but nonetheless accepted it as necessary collateral damage to repair a more pressing issue. Yet expectations were defied: the unemployment rate only inched upwards against a record-low baseline as the country continued adding jobs, albeit at a slower rate.

US unemployment rate, via Trading Economics graphing tool

In recent months, however, this resilience has been called into question. The latest revisions by the Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) revealed that the actual number of jobs added between March 2024 – March 2025 was 911,000 fewer than originally reported, making for the largest downwards revision since 2000. This comes a week after the weakest monthly employment report in recent memory which included yet another downwards revision, sending the net employment change into negative territory for June 2025 – the first monthly loss since the pandemic. What’s more, the total of 598,000 new jobs added through the first eight months of this year represents the lowest since the height of the financial crisis in 2009. Beyond the alarming time-stamp comparisons, it is natural for one to also fear that the Fed has been led astray in their decisions by misinformed data and that the economy was already on the back foot. Unchanged at 4.25% – 4.50% since the beginning of the year, the Fed rates remain above what most would consider to be “regular” for incentivizing optimal volumes of private investment, and the latest downpour of negative revisions casts doubts over whether it was truly appropriate to maintain this holding pattern. Though a rate cut on Sep. 18 is chanced at roughly 90% according to traders, there is a possibility that the Fed’s inaction has already allowed weakness to accumulate in the American labour market.

Even the jobs that were truly added raises concerns. The largest contributing sector to employment growth over the past year has been healthcare & social assistance, which maintains steady hiring even during times of economic turmoil thanks to relatively inelastic demand. It is possible that strong healthcare jobs growth – which counted for nearly half of the national total over the past year – is imparting a masking effect over less favourable hiring conditions in other industries that behave more in tandem with broader economic health. For example, manufacturing – a supposed beneficiary of the Trump administration’s protectionist agenda – suffered its fourth consecutive month of job losses in August. Similarly, retail layoffs jumped 274% year-over-year in H1, while numerous other sectors ranging from business services to leisure & hospitality are beginning to post losses in recent months while simultaneously seeing previous numbers dampened by revisions.

There is little doubt that the American labour market is finally facing a slowdown and perhaps contain more underlying weakness than initially estimated. The consolation is that it is likely not yet in a genuine contractionary phase, but rather early in a transitional period from the current “slow hiring, slow firing” stalemate before consistent job losses become reality, giving the Fed an opportunity to take timely action and avoid substantial damages. Looking longer-term, there is also hope for jobs creation through the wave of new manufacturing projects planned for the US as domestic and foreign firms alike seek to dodge tariffs and cozy up to the Trump administration, though this will take time to translate into tangible positions filled by American workers. For the near future, the job market will likely continue to soften, potentially into mild monthly contractions, but should be able to stave off catastrophic outcomes.

Tariffs & Inflation

America’s standing in global trade has long been a sore spot in Trump’s economic vision for the country. Indeed, it runs mammoth deficits against all of its major trading partners: Canada, Mexico, China, and the European Union. Moreover, the influx of foreign goods also stifles domestic manufacturing – which he equates to job creation and self-sufficiency. It was no surprise when the 47th President wrenched tariffs higher on virtually every partner nation, bringing the globally-averaged effective rate to a near-century record high of 17.4%, compared to last year’s 2.5%.

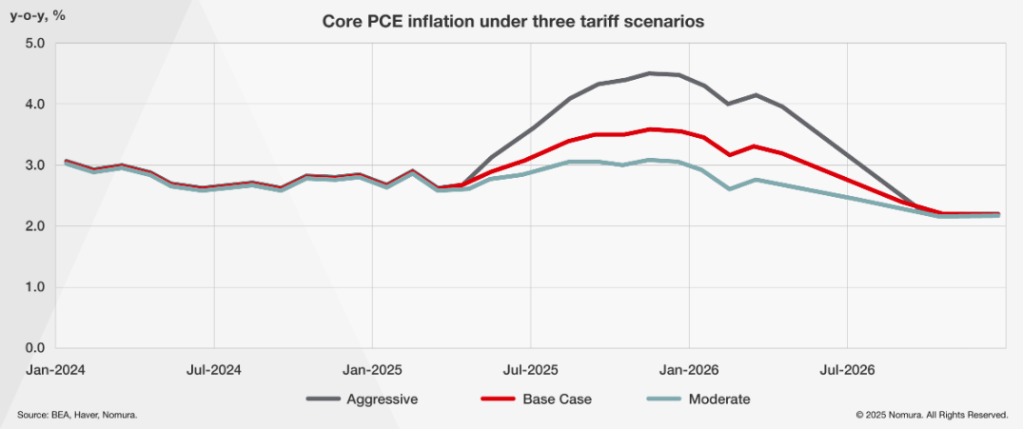

It was the expectation of most economists that the tariff onslaught would cause a surge in inflation as importers pass on extra costs to consumers via price hikes. Its actual impact on headline inflation, however, has been more muted than many had forecast. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 2.7% year-over-year in both June and July before ticking up to 2.9% in August, remaining within a reasonable range relative to the past year and safely below the runaway pace seen two years ago.

The interpretation of inflation data is tricky due to the mixed forces at play. For starters, Q1 and parts of Q2 saw pronounced “frontloading” by companies who mass-imported goods with the goal of stockpiling inventory and pre-empting upcoming tariffs. This phenomenon clearly marked itself within both GDP and trade data: Q1 saw the first quarterly GDP contraction since 2022, driven by the flood of frontloaded imports which are counted against net GDP in calculations while monthly trade deficits reached record levels between January and March. Such stockpiling likely delayed the full onset of tariff-driven inflation impacts as companies were able to stretch their ability to maintain regular pricing. Looking forward, though, it would be unrealistic to assume this cushioning effect will persist. A flurry of sellers, ranging from Walmart and Target to Home Depot and Adidas, recently announced price increases citing tariff pressures. The latest headline inflation rate of 2.9% – though not yet at frightening levels – represents the highest since January. As frontloaded inventory dwindles and companies are forced towards higher costs, it would be no surprise to see CPI year-over-year growth return above 3% sooner than later. A more important question for many, though, regards where this uptick will eventually halt. Will companies fully reach their new cost-pricing equilibrium by year-end, or perhaps by mid-2026? Will CPI growth reach 3.5% year-over-year by then, or 4.5%?

via Nomura: Forecasting the Tariff Impact on Inflation

Of course, there are a host of other factors to consider beyond simple import duties. Nomura’s projection (pictured above) considers only core inflation with energy and food items stripped. Depressed crude oil prices have translated into cheaper energy for Americans over the last year, counterbalancing other price increases in calculating the headline rate. There is also uncertainty on the extent of costs that will be passed on to consumers: so far, estimates suggest that this figure is only 22% of total costs, with nearly two-thirds being absorbed by companies themselves. The Republicans’ “One Big Beautiful Tax Bill” includes numerous provisions allocating firms billions in potential savings which could be used to offset tariff costs, whether fully or partially. Furthermore, underlying demand may not be sufficient to support significant price hikes for many sellers – consumer staples producer Proctor & Gamble warned in its latest earnings call that American shoppers are exhibiting signs of constraint and slowing down purchase frequency. Should this pattern reflect on a broader scale, firms’ abilities to pass costs on to consumers will face limitations.

On the inflation battleground that has rocked the country for the past two years, it is reasonable to project further accelerations into 2026 as importers deplete existing inventories and adjust to new costs, settling the headline CPI growth above 3%. However, the ability of companies to absorb costs themselves should not be discounted, particularly at a time when the demand outlook is unclear given red flags in other corners of the economy.

What’s the Priority?

The two topics discussed so far – the labour market and inflation – puts Jerome Powell’s Fed in a delicate balancing act. At a time when both are showing danger signs, its Board of Governors must choose a priority. At this current point in time, the latter will likely take the spotlight. Though a 3.0+% CPI growth rate is far from ideal, it does not pose the same runaway risks as seen in the post-pandemic episode. The 2021 – 2023 fiasco was fuelled by severe supply chain disruptions and an explosion of pent-up consumer demand, all exacerbated by the Fed’s initial decision to maintain near-zero rates in the mistaken belief that price spikes would quickly self-regulate. The driving factors behind the current onset of tariff-induced inflation are far weaker. Whereas entire supply chains were upended by factory shutdowns, logistical bottlenecks, and lean inventories in 2021, the impact of tariffs today do not require extreme restructuring of supply chains with cost-passing and absorbing options available to most sellers. The most probable outcome is a more moderate one-off pricing adjustment rather than the sustained inflation blowup previously seen, especially in the face of significantly more controlled consumer demand and an environment where Fed rates are already at elevated levels.

US Inflation vs Fed Rate, via Trading Economics graphing tool

By contrast, labour market weakness pose a real risk of quickly evolving into a rampant collapse. While rises in the unemployment rate has been small thus far, they have a historical tendency to aggressively surge at the onset of recessions – during the 2007 – 2009 crisis it rose from 4.7% to 10% within two years. In other words, when the signs of flaring deterioration appear, it is likely already too late. As such, even seemingly temperate softening of the labour market warrants close monitoring and – in today’s case of existing 4.25% – 4.50% interest rates – potential pre-emptive action. Given the American job market’s recent slumping signs as well as newly-unveiled underlying weakness, the Fed should strongly consider cutting interest rates at a hastened pace to safeguard against future rapid deterioration, especially considering that tariff-related inflation risks are likely to be bounded in nature, unlike its post-pandemic counterpart. Rate cuts may also produce indirect stimulus to a stagnant American housing market, which is facing sunken transaction volumes as purchasing power is stifled by restrictively high mortgage rates. Though the 30-year fixed mortgage rate typically tracks the 10-year Treasury Note, a series of Fed rate cuts will translate indirectly into borrowing cost relief for American homebuyers.

The Equities Market

If there is one corner of the American economy that has demonstrated remarkable resilience, it is its equities market. All three major stock indices broke intraday and closing records on Sep 11 & 12, continuing a historical bull run spanning the past two years. For the most part, this is justified by strong earnings: 77% of S&P 500 companies beat their EPS estimates in Q2 with the aggregated average surprise margin standing at +7%, well above the 2011 – 2019 average of +3.3%.

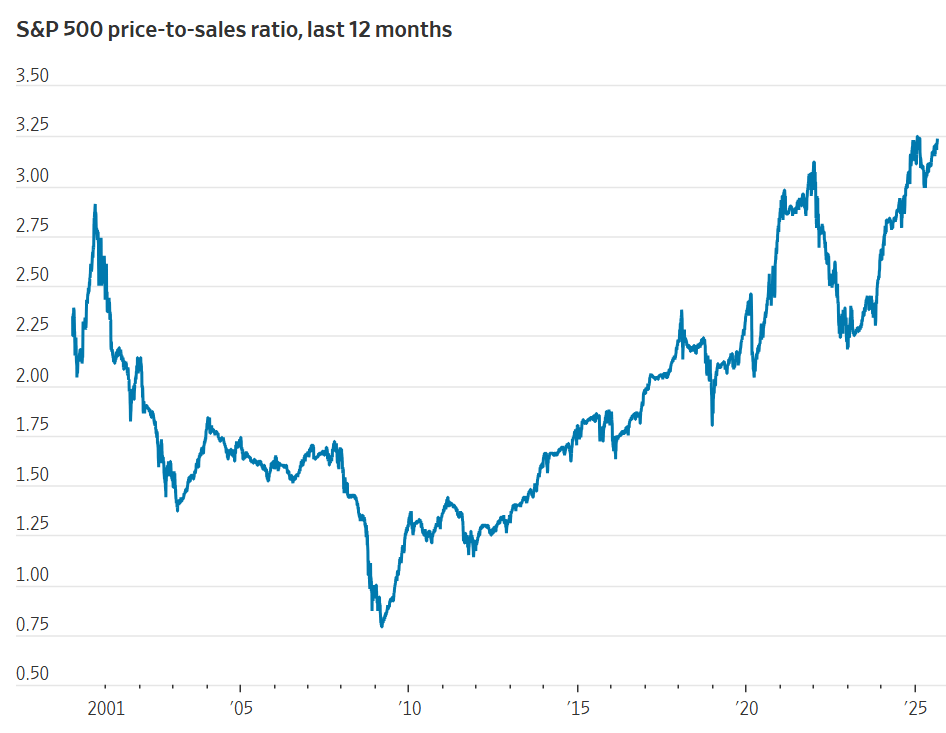

The cautionary watchouts in the stockmarket are tales of imbalances. Strong bottom-line growth have brought delight to investors, but they rob visibility from disproportionately slower revenue growth. While blended EPS results pointed to 11.7% year-over-year net income growth, revenue growth was far more modest at 4.9%, calling into question whether headline earnings should be attributed to cost-cutting and margin-widening activities more so than genuine demand growth. Indeed, while strong earnings have kept the index’s P/E ratio relatively steady, the same cannot be said for its P/R ratio – which has hit heights unseen since the Dotcom bubble in the early 2000s. Should cost reduction capacities dry up, current indications suggest insufficient underlying revenue growth to support these historical prices.

via FactSet

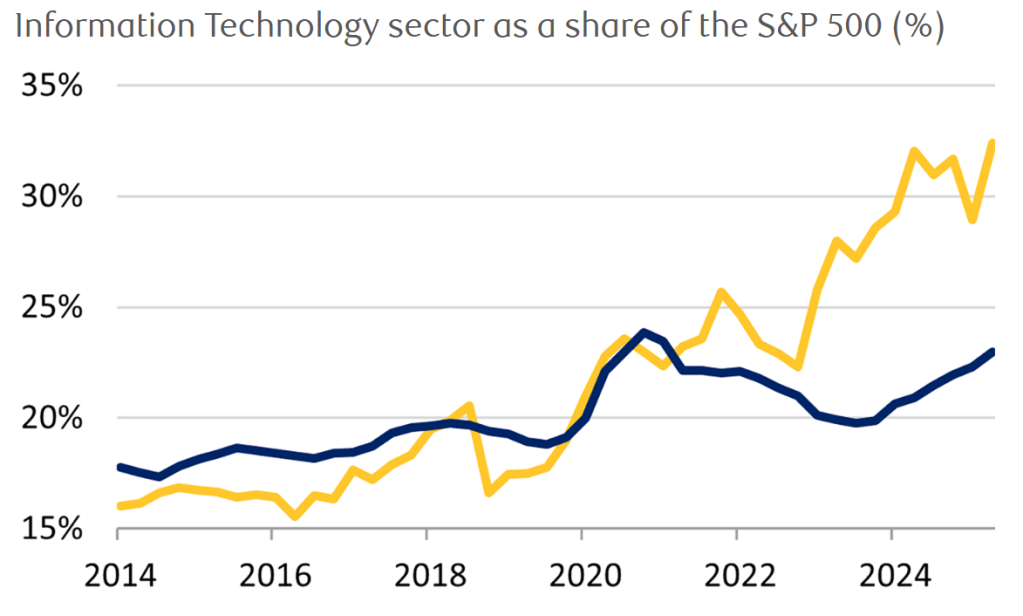

Another imbalance exists in the distribution of industries within the market’s top performers. Nearly three-quarters of the S&P 500’s Q2 earnings growth can be credited to two industries: information technologies (IT) and communication services, which have enjoyed significant propulsion from the artificial-intelligence push of recent years. However, this uneven distribution raises concerns over the true performance of the broader market. Furthermore, despite taking the lion’s share of bottom-line growth, it still may not be enough to fully justify the lopsided standing of IT companies in the American equities market. Over the last three years, their share of the S&P 500 has expanded from 22% to 32% – far outpacing their share of net income, which only grew from 21% to 23%. This unusually top-heavy and tech-concentrated layout raises concerns over excessive dependency on a technological sector that still bears many uncertainties.

via RBC (yellow: % of market cap; blue: % of net income)

Though this bull market has been supported by strong earnings, there are hints that it lacks foundational revenue growth and may be leaning too heavily on operational margin-widening efforts, which cannot be expected to remain sustainable over the long term. Additionally, the unusual concentration of tech companies within the market’s apparent performance may be masking the reality for other industries, running the risk of amplifying pullback reactions should the AI movement suffer a considerable setback in the future. All in all, the historical territories in which the American stockmarket finds itself today lacks the supporting pillars for sustainable continuity, and a correction can be expected in the near future – whether triggered by weak economic data, earnings underperformance, or some other development.

The Verdict

While the American economy has demonstrated considerable resilience, it is likely to soften in the coming months:

- The labour market may slip into narrow monthly contractions, but should be able to avoid significant losses and bounce back before year-end as the Fed cuts rates.

- Headline year-over-year inflation will likely return above 3% but shouldn’t grow uncontrolled as it did in 2021 – 2023, likely settling under the 4% pace.

- The stockmarket will suffer a pullback, possibly triggered by weaker-than-expected Q3 / Q4 earnings or pessimistic economic data.