As the global economy approaches this year’s halfway mark, there has been no shortage of turbulence for nearly every market. Crude oil futures – encompassed by Brent and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) – is no exception. On the first day of the year, WTI front-month futures closed at $73.96/bbl. Today, it sits at its lowest level since 2021 at under $63/bbl, hammered by the gloomy outlook of international trade and fears of an imminent supply surplus.

WTI Front-Month Price (via CNBC)

Death by Tariffs

US President Donald Trump’s tariffs had a marked impact on crude prices as it threatened a global slowdown in economic expansion, casting doubts over oil demand amid the prospect of reductions in shipping, construction, and manufacturing activity from stymied trade.

Trade News & WTI Futures Impact

| Date | WTI Front-Month Closing Price | Trade News |

| Feb 4 | $71.03 (-2.38%) | The US implements new 10% tariffs on all Chinese imports. |

| Feb 13 | $70.74 (-1.09%) | Trump announces plans for reciprocal tariffs. |

| March 4 | $66.31 (-2.60%) | The US implements 25% tariffs on Canadian and Mexican imports, with 10% on Canadian energy. Tariffs against Chinese goods are raised to 20%. |

| April 2 | $66.95 (-4.87%) | Trump announces “Liberation Day” reciprocal tariffs on dozens of countries, including a baseline 10% tariff on all countries. |

| April 5 | $59.58 (-2.38%) | The US implements its baseline 10% tariff. |

| May 12 | $63.67 (+4.34%) | The US agrees to suspend tariffs on Chinese imports from 145% to 30%, while China cuts their retaliatory rate to 10%. |

The slide in oil prices began due to widespread expectations over President Trump’s protectionist trade agenda even before it was officially rolled out. Despite starting the year bullishly to reach a high of $80.04/bbl thanks to concerns over supply shortages induced by sanctions on Russian energy exports, these gains were largely erased by the time of the US inauguration. Throughout February, prices were dampened by concerns over global macroeconomic conditions but remained relatively stable with front-month futures hovering around the $70/bbl mark. Although further tariffs were announced, there was still persistent expectations that deals could be reached before their official implementation – especially as a 30-day pause was given to Canada and Mexico just days after the American president signed the executive order greenlighting new duties on its neighbours. This period can be best described as a “passive cool-off” where prices were moderately suppressed in adjustment to the newfound trade uncertainty as well as slight supply increases.

Hopes of de-escalation within North America vanished when the 30-day pause expired in early March with no new deal reached with either Canada or Mexico. The official imposition of American tariffs on its closest trading partners dealt the largest-yet trade-related blow to crude prices, sinking the WTI to a 6-month low of $66.31/bbl. It was evident by this point that demand-side momentum had turned downwards as the world’s largest economy had now levied barriers against all three of its biggest trading partners. Although oil prices staged a modest month-long comeback, aided by talks of heightened sanctions on Russian and Iranian energy, market sentiment was firmly trapped in bearish territory. Ultimately, this recovery would be decimated as Trump laid out his “Liberation Day” tariff plans, wiping out 13.55% from front-month prices in 48 hours to a near 4-year low. In the weeks that followed, WTI futures tanked below the $60/bbl mark for the first time since the COVID era – breaching the average breakeven price of $62/bbl for most American producers.

Futures eventually returned north of $60/bbl following the US-China agreement to drastically scale back tariffs for 90 days in an attempt to hash out a new deal, but the difference is night and day when compared to the beginning of the year.

Supply-Side Worries

There is little doubt that trade deteriorations were responsible for the bulk of market turmoil, but downward pressures do not exist solely on the demand side. Since the start of the year, oversupply has become an increasingly more pressing threat for global crude prices. Most prominent is the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)’s decision to boost production at an accelerated rate of 411,000 BPD in May and June, whose announcement sent crude prices further down amid the tariff slide. This effectively puts the coalition 4 months ahead of schedule relative to its original plan for undoing its voluntary cuts.

Geopolitical tensions has played a balancing role on the supply side over the past year, with sanctions on countries such as Russia, Iran, and Venezuela choking supply from would-be major producers. However, these supply constraints show signs of loosening. The US is actively in talks with Iran over a new nuclear deal which, if achieved, is likely to permit the Middle Eastern producer to export more crude. The 2015 Iran JCOPA deal gave way to 1m BPD of extra production, establishing a sizeable reference if a similar deal is to be struck. Moreover, much of the short-term flareups in the Middle East that pushed temporary supply disruption fears last year – including direct strikes between Israel and Iran – have disappeared. All the while, the diplomatic push to end the Russia-Ukraine war have accelerated this month, though it is unclear the extent of loosening any ceasefire or peace agreement will bring to existing sanctions.

What’s Next?

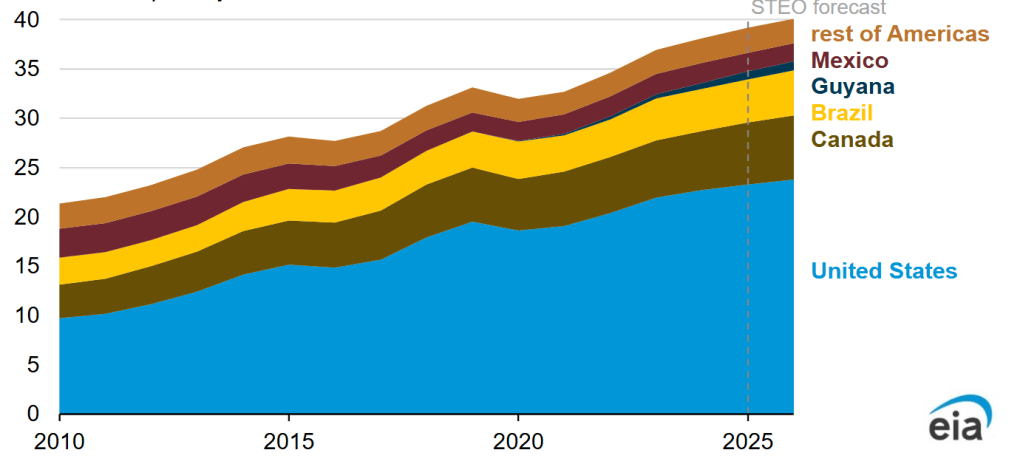

Of demand and supply side outlooks, the latter is far more predictable. Put simply, there is only one foreseeable direction for global crude supply: up. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates full-year supply growth of 1.6m BPD and 970k BPD for 2025 and 2026 respectively in its latest report, an upwards adjustment from 1.2m BPD and 960k BPD previously. Much of this rise comes from non-OPEC producers in the Americas. Though some American producers have signaled their intentions to cut spending amidst lower crude prices, this shouldn’t incur cuts in overall production thanks to improved extraction efficiencies and lowered operating costs after years of establishing infrastructure maturity – ConocoPhillips and Occidental Petroleum both announced plans to spend less this year but will maintain current production targets. Overall, US production is set to expand by 600k BPD this year and 500k BPD in 2026, with the majority coming from the Permian Basin. Canadian output – already the 4th largest in the world – is forecast to grow by 300k BPD this year and 200k BPD in the next, supported by an expansion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline that came online operationally this month which effectively triples the liquids transportation capacity from Alberta production sites to Burnaby, British Columbia for export. Several offshore projects are also due to begin production in Guyana and Brazil, expected to contribute an additional combined 300k BPD in each of the next two years.

Annual Americas petroleum & other liquids production (via EIA)

Beyond these baseline production boosts, one cannot rule out the possibility of further variable supply injections if geopolitical relations ease. The most probable scenario is the revival of an Iranian nuclear deal that sees some sanctions lifted – an ongoing negotiation which has already shaved off oil prices after news of positive developments. Last week, Trump announced the removal of all sanctions against Syria, opening the door for a resurgence in Syrian exports which, at its peak, amounted to 148k BPD. Though nowhere near the world’s biggest producers, the country benefits from a strategic geographical location in the Eastern Mediterranean with access to European markets.

It is much harder to pinpoint the exact direction of crude demand. While US tariffs have de-escalated over the last month, they remain substantially higher than before Trump took office. In its January report, the IEA forecasted full-year demand growth at 1.05m BPD. Since then, that number has been trimmed to 740k BPD, reflecting the anticipated slowdown in economic activity as a result of trade barriers. While it is unclear what the final form of US trade policy will look like, the Trump administration has thus far suggested the 10% universal tariff will remain in place regardless of progression on new trade deals, making it more likely that a new norm will be set for global economic flow rather than a reversal to freer terms of trade.

In general, it is non-OECD countries like China and India that are expected to lead global oil demand growth, which the IEA estimates at 860k BPD for this year, in contrast with a decline of -120k BPD from OECD members. China, the world’s second largest oil consumer, has shown weaker-than-expected delivery data as it struggles to boost internal economic demand. While it has been introducing a consistent stream of fiscal packages aimed at stimulating domestic activity, its manufacturing industry is feeling the bite of higher tariffs and consumer sentiments remain relatively muted. The US Energy Information Administration now projects 2025 full-year Chinese consumption at 16.53m BPD, down from its prediction of 16.74m BPD a year ago.

If the tariffs successfully achieve Trump’s goal of reinvigorating American manufacturing, the dropoff in crude demand may be cushioned. However, it is far from guaranteed that discouraging overseas production is enough to bring a true boom back home. The US already has half a million unfilled manufacturing jobs according to the Labour Department, and half of employers in the sector say they face challenges in recruiting and retaining employees. April saw a second straight month of declining US manufacturing output while a PMI of 50.2 indicated only a marginal expansion. If tariffs fail to translate into meaningful gains in domestic manufacturing, they will effectively act as an economic speedbump for the world’s biggest oil consumer. In this case, crude demand will shrivel for both superpowers on either side of the Pacific.

The Verdict

For the foreseeable future, crude prices is likely to fall further.

- Short-term global economic growth is likely to slow as a result of heightened tariffs, capping crude demand from the world’s two largest oil consumers: the US and China.

- Non-OPEC production will grow significantly with greater extraction efficiencies and newly-established infrastructure in Canada, Brazil, Guyana and other countries.

- Easing of geopolitical tensions brings the possibility of further excess supply, particularly from Iran.

- Overall, the market faces imminent short-term crude oversupply.

At the present, the oversupply threat is far from fully realized. As new production in the Americas come online and OPEC unwinds its voluntary cuts within the next 12-16 months, the extent of excess supply will be made more clear.

It is likely that the current WTI front-month price range of $60 – $65/bbl will act as the new demand-dictated equilibrium for future adjustments. Once oversupply is realized in early-mid 2026, there is a significant chance it settles under the $60/bbl threshold. Barring a major reversal of trade policies, it is a probability – not a possibility – that crude remains in a bearish mode for the next 12-24 months with the potential to fall as low as $52 – $55/bbl.